Perimenopause and Prediabetes

Perimenopause can contribute to prediabetes, which affects about 98 million American adults including millions of midlife women.

What is Prediabetes?

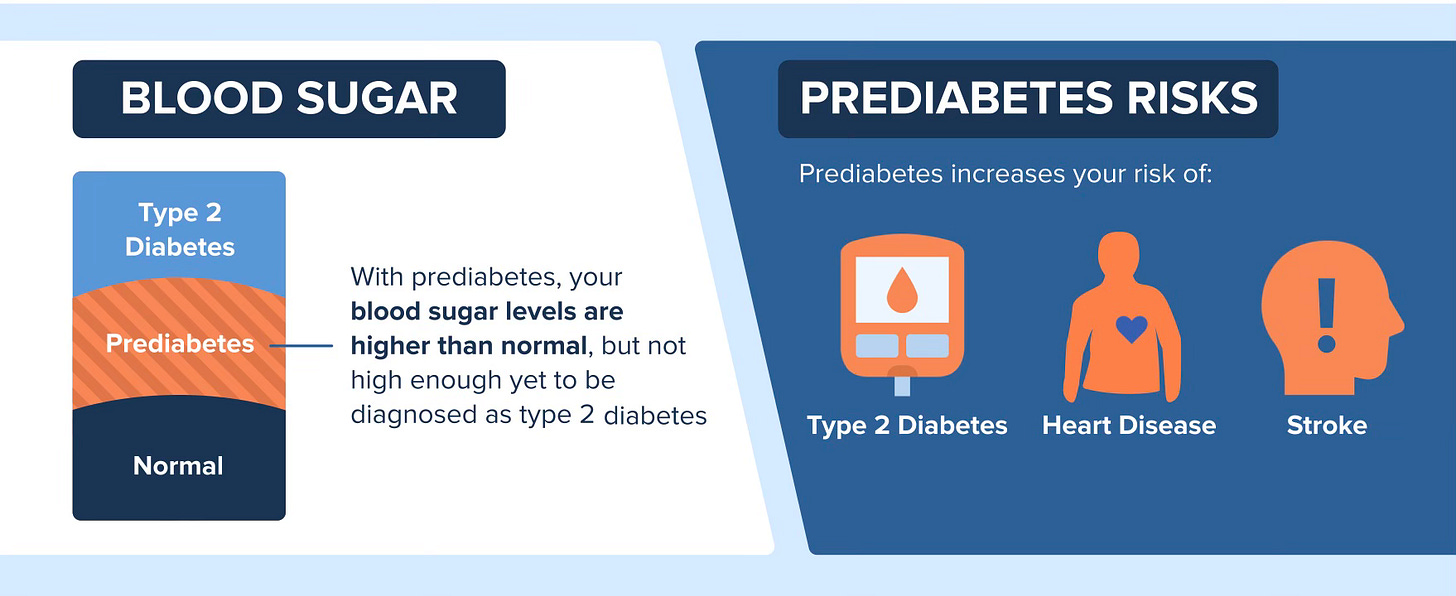

Prediabetes is when blood glucose levels (BGL) are higher than normal, but not elevated enough to qualify as type 2 diabetes. Elevated BGL can happen when your pancreas doesn’t make enough insulin to keep glucose within a normal range. More often than not, prediabetes is a result of a condition called insulin resistance that initially prompts the pancreas to overproduce insulin, causing a cascade of problems which may include weight gain.

Insulin is a hormone that acts like a key by allowing the glucose in the bloodstream into your cells where it’s used for energy right away or stored. Insulin resistance occurs when cells don’t respond like they should to the effects of insulin.

To try to correct elevated BGL, the pancreas pumps out more insulin which results in excess levels in the blood to try to get the job done. When your liver and muscles (both glucose storage hubs) are filled to capacity with glucose, the extra is sent to fat cells and stored as body fat. Eventually, the pancreas can’t keep up with the demand for insulin and BGL keep rising.

Prediabetes Problems

“Prediabetes is a red flag,” says Hillary Wright, MEd, RDN, author of The Prediabetes Diet Plan. “Learning about prediabetes, and how to prevent it, is critical for everyone, particularly midlife women.”

Prediabetes is not a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, but it is a warning sign that should be taken seriously. While having prediabetes doesn’t mean you are bound to get diabetes, calling it “pre” can diminish its potential harm.

Prediabetes increases the risk for heart disease and stroke – conditions affecting the cardiovascular system - and more. A 2020 meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Medicine that pooled the results of 129 studies with over 10 million people not only found an association between prediabetes and a greater likelihood for cardiovascular disease, but also for dying early from any cause.

Elevated BGL are harmful in several ways. They increase inflammation which contributes to the build-up of plaque in blood vessels that restricts the flow of blood to all parts of the body, most notably the heart and brain. High BGL may also hurt other organs, such as your kidneys, as well as your eyesight. Some research suggests prediabetes harms the blood vessels that nourish the retina in each eye with oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood. The retina perceives light and turns it into images so that your brain can “see” what’s around you.

When left untreated, prediabetes can progress to type 2 diabetes. Evidence shows that during a 3 to 5-year time frame, about 25% of people with prediabetes go on to develop type 2 diabetes, and upwards of 70% of those with prediabetes ultimately develop type 2 diabetes during their lifetime.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Perimenopause and Prediabetes

Perimenopause is characterized by a decline in estrogen and that may play a role in prediabetes. In one study, menopause was seen to be an independent risk factor for fasting BGL. Some research has found an increase in fasting BGL during perimenopause, which can last between 4 and 10 years. Aging is a risk factor for higher BGL, but research indicates that BGL during the menopause transition may be explained by lower levels of estrogen, which is known to support the proper function of insulin and help keep BGL within a normal range.

Changes in body composition during perimenopause may also affect BGL. Women gain an average of 1 to 1.5 pounds yearly starting in their 40s and into their 50s, according to one long-term study. The location of menopausal weight gain may affect BGL and raise other health concerns.

In midlife, extra weight tends to gravitate to the abdominal area and is likely to be mostly visceral fat. Visceral fat is found beneath the abdominal wall and surrounds the internal organs. Visceral fat is different from subcutaneous fat, which is the type of fat found on buttocks, thighs, and other places, because it produces more inflammatory compounds that are related to the risk for several chronic health conditions. This so-called “belly fat” is linked to insulin resistance, as well as higher levels of LDL (bad) cholesterol as well as an overall increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

Declining estrogen levels also affect muscle mass. During perimenopause and beyond, it’s more difficult to maintain and build muscle, which is significant from a metabolic standpoint. Muscle is the largest organ in the body and it consumes, and stores, more glucose than any other tissue, which makes it a player in regulating BGL.

Prediabetes Risk Factors

Prediabetes often goes undetected for years because its symptoms are not typically obvious. If you have one or more of the following risk factors for prediabetes, get tested for the condition in a fasted state and always find out your exact blood glucose level. (Your doctor may suggest additional tests to confirm a diagnosis.)

• You’re overweight

• Your 45 years old or older

• You have a parent or sibling with type 2 diabetes

• You lead a sedentary lifestyle

• You have PCOS

• Your blood pressure or cholesterol is high

African Americans, Hispanic/Latino Americans, American Indians, Pacific Islanders, and some Asian Americans are at higher risk for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

Gestational diabetes raises the risk for prediabetes. About 50% of women who had gestational diabetes during pregnancy go on to develop the type 2 variety. Since type 2 diabetes doesn’t happen overnight, it’s possible to have prediabetes for years before it progresses to type 2 diabetes.

Image by Jacquelynne Kosmicki from Pixabay

What to Do If You Have Prediabetes

You have prediabetes if your fasting blood glucose level is 100 to 125 mg/dl, you have a hemoglobin A1C level of 5.7% to 6.4%, or your oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is between 140 mg/dL to 199 mg/dL. You may feel fine, but please don’t ignore these numbers. Prediabetes offers you the opportunity to make changes in your diet and lifestyle.

“I sometimes hear from my patients that their physician has mentioned their prediabetes but not provided much guidance on what to do about it, but the sooner you learn how to take steps to lower your blood glucose levels, the better,” Wright says.

Here’s the good news. It’s possible to reverse the insulin resistance that causes most cases of prediabetes. You can’t do anything about your age or family history, but you may be able to alter your lifestyle to reduce your chances for prediabetes.

Having overweight or being sedentary or both is often associated with prediabetes, but small decreases in weight and more activity can yield big results. In a landmark study funded by the National Institutes of Health, people with overweight and prediabetes who lost 5 to 7% of their starting weight by improving their diet and increasing their exercise significantly reduced the chances for developing type 2 diabetes. For a 175-pound person, a 5 to 7% weight loss translates to between 9 and 12 pounds.

Following an enjoyable, balanced diet with enough calories to reduce weight (if you’re overweight) in the long-term is the best strategy during midlife and beyond. You may have heard that carbohydrate-rich foods, such as grains, fruit, and vegetables, increase blood glucose levels, but there’s no need to avoid them for lower BGL. One study found that people with a lower intake of fruit and vegetables were more likely to experience prediabetes than those with higher intakes.

Regular exercise is also part of the equation to decrease elevated BGL and keep it under control. The recommended amount of exercise is at least 150 minutes a week of brisk walking or a similar moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity on most days of the week (it’s best to spread it out), which amounts to about 30 minutes a day, five days a week. Experts also suggest at least two sessions of strength training weekly to build and maintain muscle mass.

Physical activity is the gift that keeps on giving. In addition to maintaining and building muscle, exercise positively influences insulin sensitivity (reducing insulin resistance). After exercise, muscles are more receptive to the effects of insulin as they gobble up glucose to replenish their energy stores. Research shows that even a single bout of brisk walking, jogging, or biking lowers BGL and that those beneficial effects can last for up to 72 hours. A regular exercise program is even better at providing more consistent, lower BGL as compared to less activity.

The Bottom Line on Prediabetes

Here’s why I don’t love the term “prediabetes.” For one, some people with prediabetes don’t ever develop type 2 diabetes, so how is it possible to have prediabetes? While this is more of an issue of semantics, it’s worth considering, nonetheless.

More importantly, as I said earlier there is nothing “pre” about prediabetes. That’s because damage from high BGL functions on a continuum; the higher the glucose concentrations, the greater the damage. A fasting BGL of 125 mg/dL (considered prediabetes) is no different to your body than 126 mg/dL (which is type 2 diabetes).

Calling high BGL “prediabetes” may not accurately convey the urgency of taking steps to improve the situation. In fact, the term may imply that because you don’t have a disease, there is no reason to act.

Women can live for decades after menopause (my mother lived for another 40 years!). If you have prediabetes, don’t take chances with your health. Estrogen loss increases the risk for heart disease and other conditions and nobody needs to deal with the effects of prediabetes in addition to everything else that’s going on at midlife.

Use the opportunity to do everything in your power to lower BGL to a normal range and to keep them there. A little effort goes a long way.

Let me know if you have any questions!

a very helpful article!! Thanks Hillary and Liz

Amazing summary of such an important topic. Being diagnosed with prediabetes is a critical opportunity to see the writing on the wall for diabetes risk, and a clear sign you have a chance to prevent a disease that can be controlled but not cured.